Say you’re trapped. By illness, by isolation. When I was an asthmatic kid, trapped in my parents’ trailer on hot, pollen-piled summer days, the best thing I could think of was the Cascade Mountains. We would drive from the Tri-Cities to Seattle a few times during the year, and it was so refreshing to the spirit to see the snow-capped peaks, feel the brisk air pulling into the lungs, the 70s sounds of soft rock swirling on the car radio.

It was the perfect antidote to being the youngest in a family of hard-drinking black sheep, alone in the noise of my rebellious siblings, the deep bass of my father’s jazz, the yelling between my parents. I would shroud myself in my sister’s Neil Young albums, and dream about the next time we drove over “the Pass.”

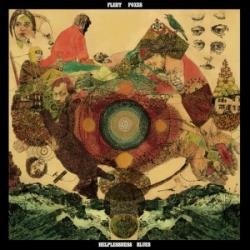

“So now I am older / than my mother and father,” Fleet Foxes‘ Robin Pecknold sings on the opening track to their new (second) (Sub Pop) album, the (Shins, Built to Spill, et al) Phil Ek-produced Helplessness Blues. “Than they had their third daughter / Now what does that say about me?” Yeah, adults seemed to get older faster back then, right? But for those of us with so many burdens, health-wise, of spirit and body, we seek that bracing clear and clean moment.

The way the barbershop-of-monk’s voices on this track float around Pecknold’s hymn to himself, in ways musicians can describe but people who write about music alas can only describe and compare. “Oh man, what I used to be? Oh man, oh my, oh me.” This is “Montezuma” and he sings of jewelry tarnished too quickly, thrown into the tomb too soon. It sounds like an endless Sunday, a kid stuck inside a house on a bright, sunny weekend day she can’t be part of. It’s all regret, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t awesomely beautiful.

“Bedouin Dress” is about debt that can’t be repaid, “the only regret of my youth.” This second song doesn’t sound like it’s heading anywhere too interesting in the first few bars, but then some weird pipes clamber about and the lyrical metaphor is extended about (eternal) returning and it’s like those alarming Paul Simon ballads about reluctant prophets that glimmered all over AM radio among the novelty songs and riff rock. “One day that’s mine,” as if the moment can be held. “In a geometric patterned dress.” You begin to notice the patterns, on returning.

The title of the album gets carried along by each track, and its obvious link to Young’s own “Helpless,” one of his most autobiographical songs. “Sim Sala Bim” is a burst of chimey exoticism closer to their long-ago debut, reminding us that Fleet Foxes did the sophomore auteur-in-the-70s-style, when rock music fans had to wait three years between masterpieces. A taste of D. Jurado is in there, though, telling us it isn’t a reissue track from a lost gem of an LP. Next up abruptly, “Battery Kinzie” thrushes with imagery of physical decay and spiritual servitude, with a timpani-driven sand march walking through the dawn (“do not wander through the dawn”).

If I was making my own high concept mix of this album to remember how I want to, the way that Scott Miller (Game Theory, Loud Family) does with Pro Tools for songs in his nifty song-by-year book “Music: What Happened,” it would probably begin on the fifth track, “The Plains/Bitter Dancer.” RIYL: Richard Thompson’s end of the rainbow falling from grace death waltzes, a more mordant Crosby Stills & Nash than your gentle bearded uncle is used to, the kind of FM transmission that chills you at the beginning of a Saturday morning in which you are to face the first day after a shattered relationship. “Tell me again my only son / Tell me again my only one,” reminding us of the rose and the briar and Lord Randall in its first half, the murdered girl, the slain love, your heart’s martyr. The second half of the medley is an Ennio Morricone gospel shuffle, the choir voices not even needing Joan Baez to accompany the finale after the execution of a couple of anarchists on screen.

“Helplessness Blues” is back to the too-smart, allergic, anti-cog of Simon’s songs, its strumming could be from an urban basketball court, sent to parents who never thought their wayward son had a chance. My own parents are dead, but I have the feeling Pecknold’s folks can hear the Nic Jones and Bert Jansch and John Jacob Niles in all of this and be proud of their depressed, so aware child. If he was my kid I would play this album over and over, giddy from a lad admitting things we wait generations for songwriters to confess. “I’ll come back to you sometime soon, myself.”

This is the center of the album (not just its initial single). That you can destroy something beautiful, or watch it being crushed and thrown into a fire and thus complicit in its demise, and know that you will benefit from this destruction. Because it means that you will have something to say, a song to sing, because something was sacrificed for you. And it may have been your own happiness. In order to remain helpless. As Nick Cave told me for the Karen Dalton In My Own Time liner notes, “Artists are salty bastards.” Sometimes salt preserves what you want to make, but is far too strong to taste for those who love us. Thus, according to the most recent issue of Uncut (in an interview with Allan Jones), we find out that Pecknold lost love during the creation of the album this song is the title track for. And he continues to wonder throughout, could there have been any other way? “Someday I’ll be like the man on the screen.” A hero, perhaps? Even merely a lover?

“The Cascades” is a string-swept space without words, in which the final half of the album begins. It starts anew with “Lorelai” which at first seems like the necessary transcendent pop song required for a wide-screen drive-in end of a decade album like this. “Norwegian Wood” and Dylan’s “Fourth Time Around” has been noted (thanks, Mr. Jones), but I hear a lot of Fleetwood Mac too, before and after Buckingham/Nicks.

This track would have probably been my first pick as a single track, even before you hear “I can see now / we were like dust on the window. I was like old news to you then.” The great thing about all these groups I’ve been comparing the Fleet Foxes to, especially Mac and Simon, is how sad and nostalgic they seem for a moment just occurring. As if you need that sadness, to make the love meaningful. The lover just out of reach must be miles and years away, for the reunion to be so warm, so wanted, so real. I once remember reading a Japanese short story about a woman who only thought about her lover when he was gone. That was the only time her heart could articulate itself, was when he was present only in memory. Wish I could remember the name of that story.

“Someone You’d Admire” sounds like it would be a positive vibes song, but but it’s really a chorale of resignation. A doomed one, at that. He probably won’t be someone you admire, is what he’s saying. Because the singer is trapped to this, to creating out of his pain and aloneness, and such a wish is as brief and hesitant to truly feel as this ballad. I once had a therapist who burst into tears — twice — because she said she pitied what my mind did to me. How it seemed to long to hurt me, to keep me from being good to myself, in her opinion. A counselor cries once, she might be having a bad day, you know? And another, a job counselor, who met with me after I got off the night shift, who said I smelled like death. I couldn’t get that out of my mind (the smell of death) and she hadn’t been emotional about it at all.

“When you talk you hardly even look in my eyes / in the morning.” This will probably be the most popular song, “The Shrine/The Argument,” which in its long, lean body cycles between near deathly quiet and big raga bursts of more timpani and chanting. “Green apples hang from the tree / they belong only to me.” This is the song that sounds most like the world’s casket lid closing, even if the earlier “The Plains/Bitter Dancer” was supposed to be the death dirge. The horns squonk and squirrel out from a black pyramid at the center of the track, like a slow dub of the ones in the Violent Femmes’ notorious track “Black Girls,” although I think Dolphy or Kenton’s cacophonous work with Bob Graettinger might have been more in mind. No resolution, either, they just scamper off like half-stepped-on scorpions into the dimming corners of a sound-desert.

“Blue Spotted Tail” is still tear-stained, but it’s a soft weeping after the long-pent burst, the blaze of sun faded behind the buildings now that you’re back in the City. Pecknold softly hums, as it trains into Wargo’s vocal arrangements for the only (near) straight-ahead rock song here, “Grown Ocean.” This would probably be the easiest place for people to begin with the album, and it’s telling about Fleet Foxes — especially now — that they chose to make it an anthemic epilogue, sweeter on the nerves and about licking wounds, but not beginning this inner odyssey with it. You have to earn it, the way that these musicians had to work so very hard to create something they would feel like owning. The most important thing to know is that they have. And now we have it, too.