{Tulia, Texas plays at the Seattle International Film Festival on Monday, June 9 at 7pm at the Harvard Exit.}

Tulia, Texas is a town outside of Amarillo with about 5,000 people who call it home. It is the county seat of Swisher County, a completely dry county and one in which over 70% of voters voted for George Bush in 2004. It is also the name and subject of an enormously compelling, hour-long documentary by filmmakers Cassandra Hermann and Kelly Whalen.

If the county bans alcohol, just how do you think they feel about cocaine?

The median income in Tulia is slightly above $27,000. The people who live there are overwhelmingly white, go to church, vote Republican and want to be left alone by outsiders. They are the people that are bitter and find comfort in guns, Jesus and antipathy towards people who are different than they are.

In 1999, an undercover police officer allegedly did a sting operation that resulted in 46 people being arrested for trying to sell him cocaine. Thirty-nine were black, amongst a population where blacks made up 8.4% of the town’s population, according to the 2000 census.

Of course, the 46 people arrested were convicted by almost exclusively white juries or pleaded guilty figuring that if they were offered 10 years in a plea bargain or faced 90 if convicted, the math would be in their favor even if justice wasn’t.

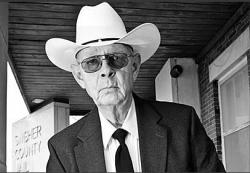

Fortunately, a defense attorney named Jeff Blackburn (who should be played by Steve Buscemi in the feature film that is reportedly being filmed about this incident) took on the case and began to notice some discrepancies. The undercover officer named Tom Coleman, a stereotypical redneck if there ever was one, reported that he performed these drug stings on days that did not correspond with his time card or that his descriptions of the alleged perpetrators varied from reality (a skinny woman was pregnant). They were all suspiciously over a gram (making for the maximum punishment by law). Knowing that small, poor communities like Tulia would benefit greatly from grants by anti-drug task forces, and that the racial and political makeup of the area made it likely he could ram through a bunch of convictions, he put together a raid on those 46 people and had them arrested for drug trafficking.

It was immaterial that no drugs were recovered as evidence or that the people arrested did not have the income that would come from selling drugs. They became felons anyway and Coleman became a hero.

The prosecution’s case begins to unravel as Blackburn looks closer at the details and finds an arrest warrant issued to (not by) Coleman for theft. As the case begins to attract more attention, the ACLU of Texas and the NAACP become involved. The case makes national news stories when Blackburn tries the case in the media before going to the courtroom.

What makes this film so important is that there is no narration. Hermann and Whalen let their interview subjects speak for themselves. Coleman, to his credit, grants an interview after he has been exposed as a fraud, criminal and racist. The interviews with townspeople are especially interesting because they are, even in retrospect, defiant and believe they did the right thing.

What the film does especially well is tell this story without getting too heavy-handed and not putting the “War on Drugs” on trial (even if it is a colossal failure by most objective standards). It highlights one example out of way-too-many and the only point the filmmakers really make explicitly is that laws need to be changed that require a higher burden of proof than only the testimony of one undercover officer (and evidence should be needed to corroborate said testimony). The film is never preachy even though it is also one-sided. Yet, it was shot in hindsight and while Hermann and Whalen knew the outcome prior to filming, they didn’t let their agenda get in the way of their story. They documented a travesty of justice and its eventual vindication but they let the participants and the facts speak for themselves.