{Chris Pureka plays next month at the Tractor on May 12th, and in Portland at Mississippi Studios on May 14th. Ramaya Soskin opens both shows.}

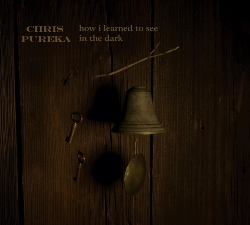

From the very first strains of Chris Pureka’s latest effort, How I Learned to See in the Dark, you’re transported into an enveloping world of the saddest songs you’ll ever love to have been hurt by. Instruments and vocals layer with dusty front porches and flickering sun through the trees, interspersed with moments of three a.m. on the bathroom floor — all with a stomping bootheel to keep the time. The songs themselves are spontaneous, precise, soul-searing and soul-saving — all at once. Pain and hope. Total clarity and utter heartache. Complete and not, locking eyes with someone across a thousand people on a Manhattan sidewalk, finding everything, and never reaching anyone.

Believe it or not, all that adjective is just at the album’s first drive-by — some hastily scrawled notes from a casual listen on a car stereo. A proper sit-down with How I Learned to See… and a decent pair of headphones yields an example of what’s becoming much too rare in our world of instant satisfactions and single-track purchases — an actual album. A recording. A start-to-finish, go-in-order, give-it-the-time-it-deserves thing — a living, breathing thing that takes on a life of it’s own as each subsequent listen merges in with the chapters of your life, song by song, year by year, line by line.

Track after track, Pureka’s songs paint landscapes that integrate seamlessly with a gorgeous composition of sound. “Wrecking Ball” grabs a hold and ushers us into the house effortlessly, a perfect setup for what lies ahead: build, crescendo, fade… while “Barn Song” and “Broken Clock” show us sightlines of sadness, of straings of regret and acceptance, and of met demands and strong backbones — a veritable modern day alt.americana orchestra that explodes full-force through the speakers. Inside a single breath, however, it all strips itself away to hand over one of the saddest (and most hopeful) love-lost standout tracks of the whole album, “Landlocked.” As we hear tales of woe and hope spun around a magically tracked acoustic, Pureka’s performance allows for the very bones of everything she’s composed here to come to life, almost tangibly, as if something is suddenly sitting right in the room with you.

The imagery and range on yet another standout track, “Song for November,” gives it the kind of legs to suit the best mixtapes ever made from here on out, regardless of subgenre preference or personal taste — because it’s true composition. It’s the very definition of music. It’s incredibly accessible, managing to translate flawlessly while staying anything but predictable. “Damage Control” eases into an explosion, another perfectly crafted crescendo of build-then-break… with a perfect slide into “August 28th” as the credits begin to roll — credits in the movie Chris Pureka has hand-crafted and permanently embedded into our personal landscapes.

It’s a vast understatement to say that there’s a lot of music out there today. An overwhelming amount, so much so that it’s easy to miss real gems in a landslide of good-enoughs and great-for-nows. But the real music, the keepers — they always manage to float to the surface and embed themselves into our personal soundtracks. Just like the people we come across, some albums are great for a few reasons, some are merely front-loaded, some stick around for a few chapters of whatever is happening to us at the moment — and some, like this one, are honest-to-goodness lifers. As Lester Bangs (by way of Cameron Crowe, by way of Phillip Seymour Hoffman) tells us in Almost Famous:

“Music, true music, not just rock ‘n roll, chooses you. It lives in your car, or alone, listening to your headphones; vast, scenic rituals and angelic choirs in your brain. It’s a place apart from the vast benign lap of America.”

This album is that music. True music. And if you just take a moment to trust in that truth, in Chris Pureka’s abilities, and take this album with you for a while, to those proverbial rooms emptied of furniture and full of memories, dust on the mantel, with a photograph someone forgot to come back for on the floor by the window — you’ll end up seeing for yourself.