When I met Óttar Birgisson and Hlynur Hallgrímsson on a Sunday afternoon in Reykjavík, they were quite literally wiping sleep out of their eyes – sleep and greasepaint. They were recovering from a Halloween party the night before; Hlynur had attended as a bust of Socrates, and the white stage makeup still lurked on his eyelids. Óttar was No-Face from the Hayao Miyazaki movie Spirited Away. He was surprised how many people didn’t get it, “Yeah, it’s a cartoon, but it won an Oscar.” Displaying shaking hands, Óttar considers whether a single night of heavy drinking could cause DTs, and announces that their next album will be titled, Too Old for Headbanging. “We might still be drunk,” he adds.

When I met Óttar Birgisson and Hlynur Hallgrímsson on a Sunday afternoon in Reykjavík, they were quite literally wiping sleep out of their eyes – sleep and greasepaint. They were recovering from a Halloween party the night before; Hlynur had attended as a bust of Socrates, and the white stage makeup still lurked on his eyelids. Óttar was No-Face from the Hayao Miyazaki movie Spirited Away. He was surprised how many people didn’t get it, “Yeah, it’s a cartoon, but it won an Oscar.” Displaying shaking hands, Óttar considers whether a single night of heavy drinking could cause DTs, and announces that their next album will be titled, Too Old for Headbanging. “We might still be drunk,” he adds.

We were there to talk about their band, 1860, and its current album Sagan. Their drummer Andri Jakobsson showed up briefly, ostensibly to help us stay on track. But staying on track wouldn’t be nearly as much fun with a pair whose conversation references Bob Ross and Elizabeth Gilbert while namechecking bands from Mumford & Sons to Cradle of Filth. The conversation ranged from American holidays {Halloween good, Valentine’s Day bad} to Honey Boo Boo {in America, if you are dysfunctional enough you get your own TV show} to Icelandic attitudes towards alcohol {Icelanders drink like American teenagers}. But I’ll try to keep the write-up related to the music. In the words of Inigo Montoya, “Let me explain. No, there is too much. Let me sum up.”

“None of us actually listen to Cradle of Filth, or really Mumford & Sons, either,” says Óttar. “That was just to be funny in an interview.”

“No, Gunnar used to listen to Cradle of Filth a lot,” Hlynur contradicts.

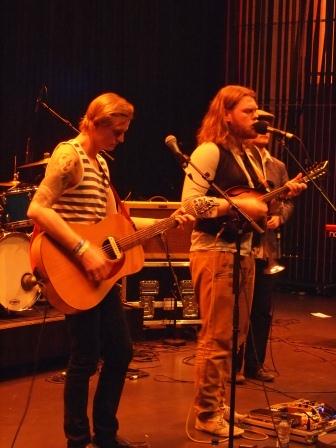

In fact, 1860 are an ensemble folk-pop band composed, like Tilbury and Of Monsters and Men, of multi-instrumentalists who all join in on infectious sing-along choruses. Notable for using mandolin (don’t call it a ukulele!) on most of their songs, they would fit on a bill with Fleet Foxes and Hey Marseilles. So basically, they are awesome.

On the band’s origins

Óttar: We don’t listen to only folk. You can only write what you know, so the more you listen to, the more you have to work from. If you only listen to one thing, then you’re just going to be the diet version of that.

The band 1860 was born out of the ashes of an indie-rock project called the Telepathetics, that didn’t actually break up.

“Never say never,” they both say. But one of the four members now lives in Denmark, another in Connecticut. So Óttar and Hlynur started 1860 as a folk-based side project with jazz pianist Kristjan Hrannar Palsson. The group grew organically, adding Andri, who continues to drum for Mammút; producer/guitar player Johann Runar Thorgeirsson; and on bass, Gunnar Jonsson, who plays clarinet for Úlfur, synths in Japanese Supershift and the Future Band, and guitar in a couple of other projects.

As I give up trying to get the names of all of Gunnar’s projects straight, Óttar comments, “Good musicians are sought after.”

Hlynur adds, “Gunnar lives and breathes music. He’s a musical genius.”

On language

Sagan is divided down the middle with the first half of the album sung in Icelandic, and the second half in English.

Hlynur: We wanted to stay true to the idea, so if the original spark was in Icelandic, we kept that. It just happened to come out evenly. There was only one song that we changed to Icelandic. We started out with “Snow Mountain Peninsula,” but it just didn’t work, so we changed it to “Snaefellsnes.” That means ‘snow mountain peninsula’ and is a real place.

On the next album

Óttar: The next album will be more coherent. We’ll try to get our act together. I listened to the album a couple days ago, and I was caught off guard. On the next one there will be more of a line through the album as a whole. The album will be more of a product than a collection of songs.

Only two or three songs on Sagan use drums. Now that 1860 has found a good drummer, they plan to have drums on all tracks of the next album to give it a more solid sound. Óttar and Hlynur do the math on drummers in Iceland: for all the performing musicians that Iceland has, they claim that maybe 100 are drummers. Of those, perhaps 30 are good. This is why Icelandic drummers are always in multiple bands.

On “Alunde” and the writing process

Tucked in the middle of Sagan is the song “Alunde.” It stands out from the rest of the album with just three voices and mandolin, and the character of the recording is unique as well. I ask if it is true that the song was recorded on a cell phone in a car. The answer? Yes.

Here’s how it happened: They thought they had something with the prechorus, but were struggling with the rest. Óttar asks, "Wasn’t it Billy Joel who said the best thing in the world is when inspiration strikes but the worst is writing intelligently about it?" They were stuck; they had worked on the song for five nights, and were getting nowhere. Then Hlynur watched a documentary that talked about the pentatonic scale, and how it was universal in music because it is inherently sonically pleasing. The documentary showed a man singing an African lullaby, “Alunde.” The song was about praising the new day, and it clicked. They wrote “Alunde” and it turned out to be about the Telepathetics falling apart.

Writing songs is a free-flowing activity for 1860. As Elizabeth Gilbert says, “You write about the ideas floating around you.” The band plays until an idea strikes, like Tom Waits driving around until he gets an idea, “picking the monster from the ether.” {Yes, they did reference Elizabeth Gilbert and Tom Waits in the same answer.} They always record their songs as soon as they finish them, capturing the spark before it’s lost so they won’t remember wrongly. But they don’t always listen to the recording while they’re working on the song. After all, like the painter Bob Ross says, “There are no mistakes, only happy accidents.” {Bob Ross! Did I mention that I love these guys?}

They feel that if the song is written too intelligently, it will be dull. Instead, they can be a little maniacal when it comes to conveying an idea; writing with heart and finishing with brain.

So they recorded “Alunde” on an iPhone in the car, and posted it to Youtube. It got the most hits of anything on their channel, and a friend in the industry heard it. He loved the rawness of the recording, and encouraged them to put it on the album unchanged.

Óttar: That backfired for us. I think it’s the most ‘skipped’ track on the album.

Hlynur: You don’t want to pay too much attention to critics, but a famous critic in Iceland said, “This is not something you put on a professional record.”

Óttar: We won’t do it again. You listen to three or four tracks and then the sound quality drops. It’s only half true that if the music is good the mediation of the recording doesn’t matter. If you don’t show more than the chord progression and the melody, people fill in the gaps themselves and can misrepresent your idea. We might rerecord “Alunde” on the next album. Radiohead had “Morning Bell” on two albums with different versions.

On being huge in Iceland

Inspired by Iceland, which works to build the Iceland tourism brand, filmed 1860 and other Icelandic artists like Mugison, Lay Low, and Seabear for a documentary. 1860 expected one of their songs to be included on the soundtrack. They gave the filmmaker their CD, and didn’t think anything more about it until one day the phone rang. Three of their songs were scattered throughout the entire film.

Hlynur: They were so serious, it was like somebody died. I think they expected us to be angry, to say, “This will not stand!”

After that, their Gogoyoko sales page went crazy. Four of the songs on Sagan have been released as singles in Iceland, and all four have made the Icelandic Top Ten. Of the four radio stations in Iceland that play pop music, three of them have played 1860. Only Of Monsters and Men and Dikta have been played on all four stations.

Hlynur: We lucked out with “Snaefellsnes.” It was second on the charts. After that, it’s easier. With a strong first single, you’ve got a toe in; they’ll play the next one.

On record labels

They established their own label, called Royal Yachting Society, to self-release Sagan. Although this has worked well for them, they aren’t sure if they will do it again. Regardless of who releases it, the next album is scheduled for release on March 14 – “Pi Day.”

Óttar: We may be decent musicians, but we’re not businessmen.

They have an opportunity with an Icelandic label, which would be convenient and offer more money up front. Having distribution makes it easier to focus on writing, but…

Óttar: There’s one label here in Iceland – not the same one. The name means “devil” in Icelandic. So you’re signing a deal with the devil.

Hlynur: There are different kinds of freedom. There’s the freedom to do what you want when you want. Then there’s the freedom to focus.

On presentation

Sagan, with its folk backbone and mandolin leads, can make you feel like you’re in a movie from the 1930s. At first, in press photos and for concerts the band wore classic tailored clothes. This old-timey aesthetic was intentional. A distinctive look helps a band stand out from the crowd and it does sell albums. A marketing study found that in Iceland, most music is purchased by moms, who usually are responsible for birthdays and other gifts. One review even called 1860 “mom-friendly pop.”

Óttar: Yes, it’s timeless, but it’s also pretentious. It gets gimmicky. So we said, “Fuck that shit.” The next album is going to be dad-friendly.