If you’re an indie pop fan but the concert marathon-long face of the Bruce canon and cult has put you off, you’re in luck: The most joyous, jittery, poetic, romantic, ramshackle, sparked up-by-punk-and-girl groups-and country Bruce Springsteen album has just been released. It’s called The Promise and it was recorded almost 35 freaking years ago though. Just as Megan Seling at The Stranger bakes yummy candy bars in yummier cupcakes, Bruce helped develop his mystery religion by creating album within album within album; there’s lost LP goodness spilling all over box sets and bootlegs if you’re hungry for his communion.

But if you have a soft spot for “Born To Run”-style typhoon-of-sound, suicide machine-near teen death and sleaze, little stuff like that has been available. Due to a horrible war he had with some business dude named Mike who tried to control his career because he had no creativity of his own, Bruce had a whale of a bummer after splashing New Jersey uber-power-pop foam in our faces and getting on the covers of too many cornball newsmagazines on the same day. Out of this darkness eventually came Darkness On The Edge Of Town, a really good album, at times (exactly 7/10) really great. It was my first and I loved the rage of “Adam Raised A Cain” but wanted more of the spank-me, wrong side of town, dirty-hotel, speed trip going raw vibe of “Candy’s Room.” Too many songs about burdens and bosses, though I thought it was cool he was trying to keep rebellion an active agent in the mainstream. But if you’re going to make a song as kind of dreary as “Factory,” at that time I thought, it should sound like something on Factory Records (such as mope-bombs Joy Division).

On the surface, the “I gotta pay my taxes?!” topics and “we have to have a talk about our relationship” blues of Darkness was all “Right On, Man!” and everything but The Ramones made me want to hit Rockaway Beach and then set fire to EMT cars taking my wasted friends to mental hospitals on orders of their parents. So I played Darkness On The Edge Of Town, actually reveling in the near-gospel yet bad-ass surge of “Badlands” — just not as much as those weird little seven inch records with the weird girls in thrift store clothes and zit-splattered skinny guys too small for their black leather jackets. Bruce must have quickly figured out how slightly alienated I was and wrote a song for The Ramones (“Hungry Heart,” his first big hit since “Born To Run”) but that was after he played about a million insanely passionate, no really Muppet-level-of-passionate, nuclear meltdown-level of passionate concerts that went on longer than Woodstock and combined the bop of Gene Vincent, and the rallying groan and yelp of Woody Guthrie and Joe Strummer, et al, and convinced everyone he was The Boss. He really was The Boss and Darkness was a very stern memo after Vietnam and maybe prophetic of the Reagan madness. Love it, but I’m not such a believer that I whip it out like The Nips on dance night here.

The Bruce cult was already in effect by then, which is one reason (of many I guess) that you may not have read this far. They actually come in different denominations: Guys who wanted Dylan to just go Iggy Pop ape-shit live and make his lyrics less oblique but still comfortably left-wing; people who loved all kids of good music but Bruce is the one big social music scene they could find a universal yammer yammer of belief in; and most recently, a lot of the indie rock “stars” you love (especially in Seattle) who write almost-noir rural story songs about death and theft and bad romance and know their way around a Bible verse or half, and may not may not have beards.

But this doesn’t excuse the people who just look at the cover of all ass-pocket Born In The USA and have a decidedly on-Rachel Flotard response to it (she lovingly mocked it, accent on “lovingly”). “Grab that butt! America! I got to get me some distressed jeans!” boys and girls squealed in 1985, genetically dividing the line nearly forever between people who occasionally increased their use of black mascara and those happy to hang out at the mall with no irony; and those who loved the serial killers rambling on in Bruce’s tales on Nebraska and people who preferred Sports like the murdering micro-manager of American Psycho. But also some people (then and now) who found the whole image a bit musty and mangy. Spingsteen could rewrite Steinbeck and Carver for those who don’t get around to reading them much; but there was no Franny and Zooey, no Oscar Wilde, and certainly no Rimbaud after Springsteen hung with his acolytes in the late 70s punk scene (that’s his backing vocals on Lou Reed’s timeless, terrifying “Street Hassle,” btw).

It’s the more quiet, usually-in-their-own-band Nebraska kind of fans, the one album in Springsteen’s pile that can be declared barbed-wire entertainment, being that it was recorded at the bottom of a coal mine when he was being lashed by genuine Vietnam veterans (OK, I made that up, he hid out in a creepy old house with only an acoustic guitar and some pen and paper and a tape recorder and had one of those Celebrity Ghost Encounter experiences, channeling Gary Gilmore and all the Reagan-era unemployed and that one guy Bruce once described as “dude always at the bar who looks as much eager to be punched in the face as he is to punch anybody”).

So the reissue of the whole Darkness On The Edge Of Town sessions is a perfect Xmas present for those guys and gals. I don’t have that damned thing, which is like a half dozen discs compact and vinyl and DVD, mostly noteworthy for the live footage from the period, where Bruce “Proves It All Night.” (That’s, um, a song on Darkness. Just so you know. Bruce kind of hates it and it would have been funny if he just released all this material and chopped it out just to be mean to it, but that’s a long back story, and I just thought it was time to mention another Bruce song title in this review.) I might buy it though if I wasn’t unemployed, and scared of the thing. (Do people really buy things this ostentatious for themselves? Good thing for The Boss it’s the holidays. What a coincidence!)

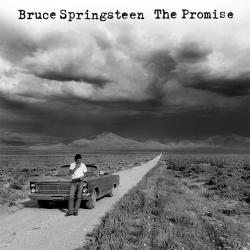

Instead, I purchased a copy of The Promise, which is the 2XCD you-haven’t-heard-these-songs guts of Darkness, and is the sticky sweet chocolate bar that was oddly baked in the dense, heavy banana nut loaf of Darkness and then chopped out. Bits of it would be spread out in Spingsteen song-batter for years; starting with Darkness itself, which wisely went with the weird and lovely “Candy’s Room” than the mid-tempo saunter down small town blocks and musing “Candy’s Boy” on here.

Don’t get me wrong, I’d love to have Darkness again, but hey, the couple dozen out-takes here are fun and strange for a Springsteen fan like me. That would be one that bought every album for years and many issues of Seattle-published Boss fanzine Backstreets but got itchy at the price tags of bootlegs. I had recently been pining to purchase an old vinyl copy of The River, which my parents gave to me for Xmas the year it came out, which I wanted again due to the Phil Spector-meets-Bobby Fuller carnival rides of “Sherry Darling,” the pinched two-chord shuffle of “Jackson Cage,” and “The River” itself, which for a pop fan like me is just as menacing as anything on Nebraska without having to bring the Ten Commandments into it and drowning the baby and all that but keeping it catchy. But The River was a double album that in a split second could have lost a whole disc with no one noticing. (Sorry cult, feel free to begin the fatwa.) Seemed too heavy to take home, you know?

The Promise gives me the analog-mastered jangle, Max Weinberg’s thundering drums, the good intentions of Darkness mixed with the pimp hat Lou Reed wore on the cover of Lou Reed Live. The story of this album is being told by rock critics as a matter of time — it’s Bruce’s time of healing, he had to work all this getting-sued-by-your-manager angst out with more frivolous sing-a-longs and love anthems (which is pretty much everything on The Promise, save for the kinda cool big old title track and hidden song “The Way”) before he could grow up big and strong on Darkness. Well, I guess, but really it’s also a matter of geography. Bruce had to leave behind all those stories about Greasy Lake and circuses and motorcycle gangs and start playing for the people he was seeing out there on tour, connecting with them as much in his art as in his day job. Also, one listen in and you can tell that The Promise sounds more like a notebook for The River than what’s left-over from Darkness. I think he really did mean to make this album, just not yet. But I’m not going to say I wouldn’t have wanted “Because The Night” and “Fire” to have been on Darkness (they were given to Patti Smith to work on, and fellow pompadour fan rockabilly Robert Gordon instead) because I really think I would have liked the LP more that way. (But I’d be quick to admit the keyboards recorded on “Because” are way too Supertramp, and Patti deflowered and sweetly kissed and sent flowers to the hell out of it far beyond what Bruce demoed.)

There’s some crazy stuff on The Promise. (He left behind the street mysticism of his first few LPs, but if you’re fans of the spirit of those this is the closest album to that you’ll find from Bruce compared to anything after the 70s.) Lyrics that start off smart and snappily reference real life, then get flat and anthemic to massage the yobs, then have a weird turn that’s just a little beyond the character of the narrator delivering it (“Waking up in a world that somebody else owns” sits near “Tonight, tonight the strip’s just right” — which no one would have said in Two-Lane Blacktop). Big gushes of mid-tempo acoustics and keyboards, which all sound suspiciously clear (yeah, some of this was recently rerecorded). “Gotta Get That Feeling” is all about, well, that feeling! He’s got to get it.

As fluffy as this is, Bruce is bouncing around with Little Steve humming this stuff, and they’re having fun, and there’s like a thousand reasons for him to be depressed right then financially and in terms of responsibility to Columbia and maybe even (as the faithful claim) to his own evolution. And “Outside Looking In” starts off like Jonathan Richman-style Buddy Holly and then Bruce ROARS like he’s back in his garage punk roots in the 60s, and then some actual damaged licks happen, and I’m simply falling for this guy all over again. Pass the Kool-Aid.