San Francisco’s John Vanderslice has worked his subtle, unique, elegant, and memorable musical magic for about eight full-lengths’ worth of material. But like many excellent writers who fill lit journals and staff picks sections of bookstores, I have always walked away from his releases craving a little more, I don’t know, danger. Vision. More happy accidents. Less concern to detail, a greater chance things might fall apart.

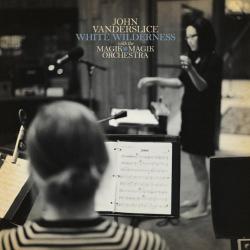

White Wilderness is his collaboration with Minna Choi and the Magik*Magik Orchestra, and just what he needed to do after hitting his singer-songwriter peak with 2009’s Romanian Names (his last album for Barsuk). I wasn’t able to hear his self-released Green Grow the Rushes EP before this debut on Dead Oceans, but the modern classical elements and instruments used to unpack or bundle up the nine songs on White Wilderness really help to make it more compelling to me than any of his earlier releases.

These are consistently somewhat sad, sober glimpses of the unsteadiness of existence, and the unity of entropy binding and crushing the world. The opening track “Sea Salt” feels like a woozy walk through the center-storm middle of a desert war zone, the cello ominously setting the protagonist up for possible cross-fire similar to images found in John Cale’s solo post-punk work. “Convict Lake” is a brilliant slice of life gone weird, a short story about an animal surprise in the midst of a broken community.

Neither of these tracks are based in regular rock instrumentation, but feature gently chaotic keys and restrained strings and a hollowed-out rhythm that threatens to fall apart with what’s being described by Vanderslice’s smoothly melodic narration. For indie-rock fans who have a hankering for Scott Walker or less-rock XTC drama, these would satisfy on both levels. The album gets even more experimental from there, though occasional freezes in the pacing (as on the title track) tests the patience for enjoying it all the way through in one sitting.

Even so, it definitely points baroque folk-rock in a much appreciated even-further experimental direction than the big operatic epics of Vanderslice’s contemporaries, showing that creative work can go deeper and quieter but demand just as much attention. And he worked up a gracious, if wasteland-chilling, set of songs to do this with on the perfectly-titled White Wilderness.