"When I gave you the Clash tape, I forgot to give you my heart. You can have it today."

"All of us are by nature wild beasts. Our duty as human beings is to become like trainers who keep their animals in check, and even teach them to perform tasks alien to their bestiality."

— Ton Nakajima

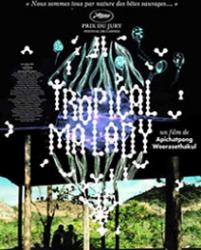

So begins Tropical Malady, emerging master Apichatpong Weerasethakul's deliriously original and unequivocally brilliant Cannes Jury Prize winner about, among countless other things, the relationship between simple country farmboy Tong (Sakda Kaewbuadee) and hunky soldier Keng (Banlop Lomnoi). The two become acquainted early on, and we then follow them around their rural Thai village as they take walks, go to the movies, visit a mysterious cave, play little slap-n-tickle games. And all the while, their friendship is blooming into a kind of effortless desire.

It's so charming, so tender, and told with such an easy romanticism that a couple of truly heartrending moments are likely to catch you off your emotional guard. One ravishingly pure instant in particular (see top quote) may just touch previously-unreachable places in your cynical lil' heart.

The moment in which Tong and Keng come closest to consummating their relationship arrives in a shockingly intimate scene involving something that's, well, finger-lickin' good. And just as you begin to feel guilty for not looking away, a catchy pop tune suddenly begins to play over beautifully-rendered day-to-day shots of Keng; there's such a sense of conclusion here that you expect the closing titles to begin at any moment.

But that's only one hour in. When you see the film — and have I gotten across that you really must? — pay close attention to the things that seem out-of-place in the early scenes: what the soldiers find in that seemingly endless field; the enigmatic naked man walking down a lonely road; offhand dinner-hour conversations about a corpse's transient ghost. Perhaps they'll make sense later, after Tropical Malady literally ruptures at midpoint and even assumes a new title, A Spirit's Path.

And this is the part of the film that tends to give people problems, so let me just warn you now that your patience might be tested. After a brief recounting of a Thai folk legend about a shapeshifting animal shaman (the tale will continue periodically with the help of intertitles and slate drawings), we get a lot of wordless footage of the soldier (played again by Lomnoi, but whether he's still Keng is up for discussion) walking around a forest, removing leeches from his body, foraging for food, tracking a mysterious tattooed creature (Kaewbuadee, formerly Tong)… and receiving sage advice from a talking baboon. There are long stretches in which not much seems to be going on, but every frame positively glows with magnificent beauty and elusive, indefinable insight.

And this elusiveness is the key: I can't explain to you how or why, but the bewilderment you may feel is part of the serenely numinous wisdom this film conveys. I've come to believe that A Spirit's Path is a transmigration (and, some have argued, a retelling) of the Keng/Tong love story into the metaphysical realm. And it's only through this über-confident directorial approach that Weerasethakul can so effectively force us to meditate on the painful, jubilant, perplexing malady that afflicts us all.

But my words can never do righteousness to this enchanted film, and to burden you with my thoughts on what it all means would rob you of discoveries I want you to make on your own. (Anyway, my interpretations tend to alter with each viewing.) So let me put aside the sheer reverence I feel and try a different approach now.

I am hopelessly fucked up over Tropical Malady. It holds me in its grasp like an old lover I just can't shake: Since the first time I saw it (nearly three months ago), not a day has passed when it hasn't popped into my mind without warning. When I see or hear its name, my heart skips a beat, giving way to that weird twinge of longing hesitation. My eyes water when I read old love letters I've written to it. I Google its name a lot more than I should. And not just because I can't think of a better, more affecting, more sublimely audacious piece of cinema produced so far this century.